Background - Computer Music Programming Languages¶

What is Computer Music Programming?¶

To frame the discussion of the motivation and goals of the Scheme for Max project, I will first briefly survey the computer music programming landscape, discussing several families of language, their approaches to programming computer music, and the advantages and disadvantages of these for various kinds of user and projects.

To begin, I would like to clarify exactly what I mean by computer music programming. I am using the term to refer to programming in which both the tools used and the composition itself are programmed on a computer. I say this using the word composition in its broadest sense - a composition could be a linearly scored piece of set length and content, or a program with which a performer interacts, but that contains prepared material of some kind. This is distinct, for example, from commercial music tools (such as sequencers or digital audio workstations) in which a computer program is run as the host environment, but the compositional work itself is stored as static data within that program (for example in a binary format or in MIDI files), and would not normally be considered a computer program itself.

Using this definition of computer music programming, we can draw a further distinction between two kinds of programming and programmer: we have programming that is specific to a composer or an artistic work; and we have programming of tools and frameworks that will be potentially be used by many people and in potentially many contexts. For the purpose of this discussion, I will refer to the people doing these as the composer-programmer - a term also used by Curtis Roads in “Composing Electronic Music” (Roads 2015, 341) - and the tools-programmer (my own terminology). Of course, these are frequently the same person at different times. This distinction is important, as the goals of these two programmers, and thus the ideal design of supporting technology, can be very different. The composer-programmer likely wishes the programming tools to be as immediately convenient to an individual as possible, while the tools-programmer may be developing software for use by a larger community and may prefer design decisions that favour long-term code reuse and team development at the expense of immediate convenience. As we will see, the various computer music languages, platforms, and approaches favour one of these hypothetical programmers to a greater or lesser degree. Beyond these distinctions, I use the term computer music programming as broadly as possible - I include as computer music programming platforms both graphic platforms with which a beginner can be immediately productive as well as general-purpose programming languages that are the domain of experienced computer programmers.

Requirements for a Computer Music Platform¶

Prior to examining the programming platforms, let us examine some common requirements of the composer-programmer so that we can assess how the various options meets these needs. While the list of possible requirements is long, I will group them into three high-level requirements that are personally important to me as a composer and performer. Note that not all of these are necessarily fulfilled well, or at all, by each of the possible platforms a composer might use - some offer only partial support for a requirement, or perhaps even none at all (Lazzarini 2013, 97).

Support for Musical Abstractions¶

To be maximally productive in producing musical works, a computer music language should provide musically meaningful abstractions that support how a composer thinks about music. Examples of these abstractions would be programmatic constructs for representing notes, scores, instruments, voices, tempi, bars, beats, and the like. The more of these that are supported in the language itself, the less the programmer must decide and code themselves in order to make music. Probably the most important of these abstractions are those concerning musical time - a good computer music language must have an implementation of logical time, allowing the programmer to schedule events accurately in a way that makes sense to the user but that also works for rendering or playing in realtime with a degree of accuracy appropriate for music (Dannenberg 2018, 3).

However, it should be noted that the importance of these abstractions being readily provided by a language varies widely amongst composer-programmers: while some composers will be relieved not to have to decide how to implement the concept of beats and tempi themselves, others may be expressly looking for platforms that do not come with any assumptions of how one might think about musical abstractions. Computer music programming languages thus also vary widely in their areas of focus and the problems they attempt to solve for the programmer (Dannenberg 2018, 4). For example, the Csound language comes with a built-in abstraction of a score system, that in turn depends on abstractions representing beats and tempi (Lazzarini 2016, 157). In contrast, the Max platform takes the design approach of giving the user an almost blank canvas, deliberately avoiding any assumptions that the user will make music of any particular style or in any particular way (Puckette 2002, 34).

For my own purposes, I would ideally like to have the ability to score conventional music without necessarily being required to implement all the dependencies of a score system myself, but I would still like to have the flexibility of being able to implement my own score system should a given piece warrant it, and to have the option to greatly alter the abstractions that come with a language when I choose to do so. My personal yard stick is to ask whether I could reasonably program and render a piece such as “Ionization” by Edgard Varèse, with its shifting meters and cross-rhythms between instruments - an endeavour which would be frustratingly difficult on standard commercial tools.

Support for Performer Interaction¶

A modern computer music platform should make it possible for a performer to interact with a piece while it plays. Various computer music languages support interaction through manipulating a computer directly (through text, network input, or graphical devices), through physical input devices such as MIDI controllers and network-connected hardware, and even through audio input, allowing the performer to interact with the program by playing an acoustic instrument.

Again, the importance of this varies with the composer and the platform. In fact, this was not even possible with early computer music languages such as the MUSIC-N family, with which the process of rendering audio from a score file took far longer than the duration of a piece (Wang 2017, 60-63).

However, since the advent of realtime-capable systems, this has become a standard feature in computer music platforms. In fact, in contrast to the Music-N languages, the Max platform was designed to support performance-time interactivity first, with the ability to render audio only added later as computers became capable of doing both (Puckette 2002, 33). As someone who comes principally from a jazz and contemporary improvised music background, being able to create complex systems that support realtime input is a central requirement.

Support for Complex Algorithms¶

Finally, a powerful computer music programming platform should support programming algorithms of significant complexity. It should be possible to make the platform, for example, do things that are impractical or impossible for the human performer or for the composer working at a piano with score paper. My personal goals include creating music that combines algorithmically generated material with traditionally scored and improvised material. For my algorithmic work, I want to explore techniques and forms that would be impractical if one is individually entering notes, thus instead requiring programmatic implementation of algorithms. However, it is also important to me that a performer be able to interact with the algorithms. That, to quote Miller Puckette on his original design goals for Max, basic musical material should be “controllable physically, sequentially, or algorithmically; if they are to be controlled algorithmically, the inputs to the algorithm should themselves be controllable in any way” (Puckette 1991, 68).

While one could certainly come up with further requirements, these three high-level requirements provide the basis on which I will discuss the main families of computer music programming tools, and around which we can discuss how Scheme for Max complements existing options.

Computer Music Platform Families¶

For the purpose of keeping this discussion within a reasonable length, I will likewise categorize the historical and currently popular computer music programming environments into three general categories: domain-specific textual languages, visual patching environments, and general-purpose programming languages that are run with music-specific libraries or within musical frameworks.

I will briefly discuss each of these, listing various examples, but focusing on a representative tool from each family. I will provide my observations and experiences of the advantages and disadvantages of each, drawing both on the literature and on my personal experiences with tools from each category over the last 25 years.

Domain-Specific Textual Languages¶

A domain-specific language (DSL) for music is a textual programming language intended expressly for making music with a computer (Wang 2017, 58).

The first historical example of programming computer music (that one might reasonably consider as more than an audio experiment) used a music DSL, namely Max Matthew’s MUSIC I language, created in 1957. MUSIC I (originally referred to as simply MUSIC) was a domain-specific language written in assembly language for the IBM 704 mainframe at Bell Labs. It was able to translate a high-level textual language with musical abstractions to assembly code, and could (through various intermediary steps) output digital audio. MUSIC I was followed by various refinements by Matthews (Music II through V), and by similar languages by others. Its lineage continues to this day in the Csound language, still under active development and widely used, and one with which I have extensive experience (Manning 2013, 187-189).

While the source code of a Csound piece is clearly a computer program (and would be recognizable as such to one familiar with programming) the way in which it turns code into music would not likely be obvious at a glance to a programmer unfamiliar with music. The language is, to a significant degree, designed around high-level abstractions suitable for particular ways of creating a composition, and has a particular way in which it is run to make the final product. Historically, running such a program meant rendering a piece to an audio file, but with modern computers (and versions of Csound) the rendering can be done in realtime, streaming audio output rather than writing to a file. While originally these programs were not something with which a performer could interact while the music rendered, facilities now exist in Csound for performers to interact with the programs while they play (Lazzarini 2016, 171-179).

In addition to Csound, some other actively developed examples from this general family of language include SuperCollider, ChucK, and Faust, each of which has a particular focus or approach to the problems of computer music (Wang 2017, 69-72; Lazzarini 2017, 41-42).

A notable advantage of a using a music DSL is that many of the hard decisions that face the programmer have been made already. The composer-programmer is not starting with a blank slate: the language provides built-in abstractions ranging from macro-structural concepts such as scores and sections to individual notes and beats. Music DSLs thus significantly simplify the task of programming music and reduce how much the composer-programmer must learn and program to begin making music (Lazzarini 2017, 26). In Csound, for example, a program consists of an orchestra file, containing programmatic instrument definitions, and a score file, containing a score of musical events notated in Csound’s own data format. (These files may be merged into one unified csd file, but the distinction still holds.) These are used together to render a scored piece to audio, either as an offline operation or as a realtime operation. A sample of Csound code is shown below, with an instrument playing a short scale driven by the score.

<CsoundSynthesizer>

<CsInstruments>

instr 1

; take pitch as midi note from param 4

kfrq mtof p4

; use freq to create a saw wave at 0.8 amplitude

asig vco2 0.8, kfrq, 0

; create an ADSR envelope

aenv 0.01, 0.3, 0.7, 0.2

; apply the env and output in stereo

outs asig * aenv, asig * aenv

endin

</CsInstruments>

<CsScore>

; time dur midi-note-num

i1 0 1 60

i1 1 1 62

i1 2 1 64

i1 3 1 65

i1 4 1 67

</CsScore>

</CsoundSynthesizer>

With their built-in musical abstractions, DSL’s are attractive to the composer-programmer, but on the other hand, the tools-programmer is significantly more constrained than when working in a general-purpose programming language. This can be frustrating for experienced programmers coming from general-purpose languages, who may wonder where their function calls and looping constructs went and how they can express the algorithms with which they are familiar in the unusual abstractions provided by the language. For example, in Csound one can program a form of recursion, but one of the techniques for doing so involves creating instruments that play notes that in turn schedule notes (Lazzarini 2016, 116). The use of the note as the fundamental unit of computation (where a “note” is an instance of an instrument definition activated at some time, for some duration) requires the tools-programmer to not only understand the concept of recursion, but to also understand how to translate it into this unusual syntax.

Music DSLs generally provide ways of extending the language with a general-purpose language, allowing the tools-programmer to add new abstractions to the DSL itself. In Csound, for example, a tools-programmer may create a new opcode (essentially the equivalent of a Csound class or function) using the C language, compiling it such that it can be used in the same way as any built-in opcode that comes with Csound (ffitch 2011b, 581).

It should also be noted that the ease with which composer-programmers can work with DSLs has led to broad popularity in the music community, and this in turn has led to many programmers creating publicly-available extensions, thus providing a rich library of freely-available tools for the programmer to use. Csound, for example, is still actively used and developed today, which is remarkable for a language first developed in 1986, and now has thousands of objects available (Manning 2013, 189). If an extension is popular and useful enough, it may even find its way into the main language or into official repositories of extensions.

So how does a music DSL such as Csound stack up with regard to our three high-level requirements? Certainly, we are given many high-level and convenient, musically-meaningful abstractions. Creating linear pieces according to a set score is straightforward. Performer interaction is also possible in modern versions, though programming an interactive system is somewhat cumbersome in that tasks that would require simple programming in a general-purpose language must be done in an unusual manner to fit in the note-centered paradigm of Csound. For example, making a component to receive, parse, and translate MIDI input according to some arbitrary rules requires making an “instrument” and having the score turn on “always-on” notes (Lazzarini 2016, 175). Clearly, we are bending the built-in abstractions to other purposes, an in this context, they come at the expense of easily comprehensible code.

Likewise, expressing complex algorithmic processes can be difficult. Being a textual language, expressing mathematical formulae is straightforward. But anything truly complex (for example, building a constraint system incorporating looping, sorting, and filtering) is discouragingly cumbersome. Absent regular functions and iteration, these kind of ideas can be very difficult to express, requiring a great deal of code that is subverting the design of the language.

Returning to our distinction between the composer-programmer and the tools-programmer, one could say that music DSLs are heavily optimized for the composer-programmer and for the process of composing a (relatively speaking) traditional linear piece. Or, to put it another way, Csound and its like are appropriate for making pieces, but cumbersome for making programs.

Visual Patching Environments¶

A quite different family of computer music languages comprises the visual “patching” environments, such as Max and PureData (a.k.a. Pd). First created by Miller Puckett while at IRCAM in 1985, Max was designed from the outset to support realtime interactions with performers. In a typical use case, the Max program would output messages (which could be MIDI data, but were not necessarily), and these would be rendered to audio with some other tools, such as standard MIDI-capable synthesizers or other audio rendering systems. Later versions of Pure Data and Max added support for generating audio directly, as computers became fast enough to generate audio in real time (Puckette, 2002, 34).

In Max and Pure Data, the composer-programmer places visual representations of objects on a graphic canvas, connecting them with virtual “patch cables”. When the program (called a “patch”) runs, each object in this graph receives messages from other connected objects, processes the message or block of samples, and optionally outputs messages or audio as a result. A complete patch thus acts as a program where messages flow through a graph of objects, similar to data flowing through a spreadsheet application. The term “dataflow” has been used to describe this type of program (Farnell 2010, 149) though it should be noted that Miller Puckette himself asserts that it is not truly “dataflow” as the objects may retain state, and ordering of operations within the graph matters (Puckette 1991, 70).

As with many textual DSL’s, it is possible for the advanced programmer to extend both Max and Pure Data by writing externals (extensions) in the C and C++ languages. In Max, the tooling for this facility is called the Max Software Development Kit, or SDK (Lyon 2012, 3). The popularity and extensibility of Max and Pure Data has led to thousands of patcher objects being available for Max and Pure Data, both included in the platforms and as freely-available extensions. These include objects for handling MIDI and other gestural input, timers, graphical displays, facilities for importing and playing audio files, mathematical and digital signal processing operators, and much more (Cipriani, 2019, XI).

This visual patching paradigm differs significantly from that of Csound and similar DSLs. The program created by a user is best described as an interactive environment, rather than a piece. A patch runs as long as it is open, and will continue to do computations in response to incoming events such as MIDI messages, timers firing, or blocks of samples coming from operating systems audio subsystem (Farnell 2010, 149).

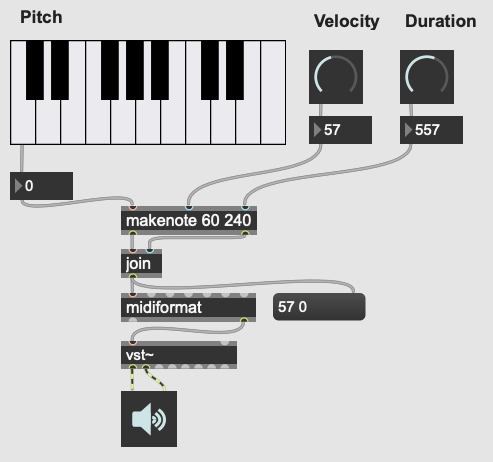

Figure 1: A Max patch with a keyboard and dial user interaction objects.¶

In contrast to textual DSLs such as CSound, patching environments have comparatively little built-in support for musically meaningful abstractions. There is no built-in concept of a score, or even a note, and there is no facility for linearly rendering a piece to an audio file from some form of score data store. If the programmer wants such things, they must be built out of the available tools. In this sense, these environments are more open-ended than most DSLs - one builds a program (albeit in a visual manner) and this program could just as easily be used to control lighting or print output to a console in response to user actions as to play a piece of music. And indeed, modern versions of Max and Pure Data are widely used for purely visual applications as well as music, through the Jitter (Max) and Gem (Pd) collections of objects. While these come with many objects useful for making music, there is nothing intrinsically musical about the patcher environments themselves. As Max developer David Zicarelli put it in his paper on the seventeenth anniversary of Max, it is, compared to most programs, “a program which does nothing”, presenting the user with a completely blank canvas (Zicarelli 2002, 44).

Returning to our requirements, the fundamental strength of patching environments is the ease with which one can create programs that support performer interaction. A new programmer can realistically be making interesting interactive environments that respond to MIDI input within the first day or so of learning the platform.

However, making something that is conceptually closer to a scored piece is much more difficult than in a language such as Csound. It is most definitely possible, but it requires the programmer to be familiar with the workings of many of the built-in objects, and to make a substantial number of low-level implementation decisions, such as how data for a score should be stored, what constitutes a piece (or even a note!), how playback should be controlled or clocked, and so on.

Implementing complex algorithms is also a difficult task in the patching languages. The dataflow paradigm is unusual in that it requires one to write programs entirely using side-effects. Objects do computations in response to incoming messages, which, under the hood, are indeed function calls from the source object to the receiving object, but the receiving objects have no way of returning the results of this work to the caller - they can only make new messages that they will pass on to downstream objects, resulting in more function calls until the chain ends. Describing this in programming terminology: the flow of messages creates a call chain of void functions, with the stack eventually terminating when there are no more functions to be called, but no values are ever returned up the stack.

While easy to grasp for new programmers, this style of programming makes many standard programming practices difficult to implement, inluding recursion, iteration, searching, and filtering. Thus, much like the musical DSLs, but for a different set of reasons, complex algorithms that would be straightforward in a general-purpose programming language can require significant and non-obvious programming.

General-Purpose Programming Languages¶

Our third family of computer music programming languages is that of general-purpose programming languages (GPPLs), such as C++, Python, JavaScript, Lisp, and the like. The use of GPPLs for music can be divided broadly into two approaches, corresponding to the mainstream software development approaches of developing with libraries versus developing with inversion-of-control frameworks.

In the library-based approach, the programmer works in a general-purpose language, much as they would for any software development, and uses third-party musically-oriented libraries to accomplish musical tasks. In this case, the structure and operation of the program is entirely up to the programmer. For example, a programmer might use C++ to create an application, creating sounds with a library such as the Synthesis Tool Kit (Cook 2002, 236-237), handling MIDI input and output with PortMIDI (Lazzarini 2011, 784-795), and outputting audio with the PortAudio library (Maldonado, 2011, 364-375). While the use of these libraries significantly reduces the work needed by the programmer, fundamentally they are simply making a C++ application of their own design.

In the second approach, a general-purpose language is still used, but it is run from a musically-oriented host, which could be either a running program or a scaffolding of outer code (i.e., the host is in the same language and code base but has been provided to the programmer). The term “inversion-of-control” for framework-based development of this type refers to the fact that the host application or outer framework controls the execution of code provided by the programmer - the programmer “fills in the blanks”, so to speak. Non-musical examples of this are the Ruby-on-Rails and Django frameworks for web development, in which the programmer need provide only a relatively small amount of Ruby or Python code to create a fully functional web application. A musical example of this is the Common Music platform, in which the composer-programmer can work in either the Scheme or Common Lisp programming language, but the program is executed by the Grace host application, which provides an interpreter for the hosted language, along with facilities for scheduling, transport controls, outputting MIDI, and so on (Taube 2009, 451-454). The framework-driven approach thus significantly decreases the number of decisions the programmer must make and the amount of code that must be created, while still preserving the flexibility one gains from working in a general-purpose language.

While the framework-oriented approach is less flexible than the library-oriented approach (given thatthe programmer must work within the architectural constraints imposed by the framework), the strength of GPPLs compared to either textual DSLs or visual patching platforms is in both cases flexibility, especially with regard to implementing complex algorithms. With a general-purpose language, the programmer has far more in the way of programming constructs and techniques available to them. Implementing complex algorithms is no more difficult than it is in any programming language. Looping, recursion, nested function calls, and complex design patterns are all practical, and the programmer has a wealth of resources available to help them, drawing from the (vastly) larger pool of documentation available for general-purpose languages.

Of course, this comes at the cost of giving of the programmer both a great deal more to learn and a lot more work to do to get making music. In the library-based approach, it is entirely up to the programmer to figure out how they will go from an open-ended language to a scored piece, and even in the framework-driven approach, the programmer begins with much more of a blank slate than they typically do with a musical DSL.

General-purpose languages are thus attractive to composers wishing to create particularly complex algorithmic music, or to those wishing to create sophisticated frameworks or tools of their own that they will reuse across many pieces. With general-purpose languages, the line between composer-programmer and tools-programmer is blurred, and indeed, managing this division is one of the tricker problems with which the programmer must wrestle.

General-purpose languages can also provide rich facilities for performer interaction, but again, at the cost of giving the programmer much more to build. Numerous open-source libraries exist for handing MIDI input, listening to messages over a network, and interfacing with custom hardware. However, the amount of work and code required to use these is significantly higher than doing the same thing in a patching environment. It is worth noting that, relatively speaking, the additional work required decreases as the complexity of the desired interaction grows. Given a sufficiently complex interactive installation, at some point the trade-off swings in favour of the general purpose language. Where precisely this point is depends a great deal on the expertise of the programmer - to a professional C++ programmer, the savings of using a patching language may be offset by the power of the (C++) development tools with which the programmer is familiar.

Multi-Language Platforms¶

Finally, we have what is, in my personal opinion, the most powerful approach to computer music programming: the multi-language, or hybrid, platform. As programming tools and computers have improved, it has become more and more practical to make computer music using more than one platform at a time in an integrated system.

This multi-language approach has been explored in a wide variety of schemas. The simplest is that of taking the output from one program and sending it as input to another. With the Csound platform, this is straightforward: instrument input, whether real-time or rendered, comes from textual score statements, and these can be created by programs made in other languages that either write to files or pipe to the Csound engine (ffitch 2011a, 655). In many modern platforms tighter integrations are now possible through application programming interfaces (APIs) that let languages directly call functions in other languages, as they run. One can, for example, run Csound from within a C++ or Python program, interacting directly with the Csound engine using the Csound API (Gogins, 2013, 43-46). One can also run a DSL such as Csound inside a visual patcher, using open-source extensions to Max and Pd that embed the Csound engine in a Max or Pure Data object (Boulanger 2013, 189). One can run a general-purpose language alongside a DSL or visual platform using a bi-directional integration layer, such as is done with Node for Max (a part of Max), or with Julien Vincenot’s MozLib, which enables interacting with Common Lisp from a Max patch. And finally, one can even run a general-purpose language inside a DSL or visual platform, such as Python inside Csound (Ariza 2009, 367) or JavaScript inside Max (Lyon, 13).

Note that a multi-language platform differs from the previously discussed practice of extending a patching language or DSL with a GPPL such as C or C++. In the multi-language hybrid scenario, the embedded GPPL is used by the composer-programmer to make potentially piece-specific code, rather than solely by a tools-programmer who is creating reusable tools in the environment’s extension language. (It should be mentioned, however, that it is feasible for an advanced programmer to prototype algorithms in an embedded high-level language such as JavaScript and port them later to a DSL’s extension language, should they reach sufficient complexity and stability to warrant the low-level work.)

In the hybrid scenario, the combination of the various platforms provides the programmer with a tremendous amount of flexibility (Lazzarini 2013, 108). One can, for example, use visual patching to quickly create a performer-interaction layer, have this layer interact with a scored piece in the CSound engine, and simultaneously use an embedded GPPL to drive complex algorithms that interact with the piece.

The cost of this approach is simply that it requires the programmer to learn more - a great deal more. Not only must they be familiar with each of the individual tools comprising the hybrid, but they must also learn how these integrate with each other. This necessitates not just learning the integration layer (e.g., the nuances of the csound~ objects interaction with Max), but likely also understanding the host layer’s operating model in more depth than is required of the typical user. For example, synchronizing the Csound score scheduler and the Max global transport requires knowing each of these to a degree beyond that required of the regular Csound or Max user.

Nonetheless, the advantages of the hybrid approach are profound. The hybrid programmer has the opportunity to prototype tools in the environment that presents the least work, and to move them to a more appropriate environment as they grow in complexity or once their design is sufficiently tested. Numerous performance optimizations become possible as each of the components of the hybrid platform have areas in which they are faster or slower. Reuse of code is made more practical - experienced programmers moving some of their work to GPPLs can take advantage of modern development tools such as version control systems, integrated development environments, and editors designed around programming. And finally, the complexity of algorithms one can use is essentially unlimited.

Conclusion¶

It is in this multi-language, hybrid space that Scheme for Max sits. S4M provides a Max object that embeds an interpreter for the s7 Scheme language, a general-purpose language in the Lisp family (Schottstaed n.d.). With S4M, one gets a general-purpose language in a visual patcher, and with objects such as the csound~ object, can interact closely with a textual DSL as well.

Given the myriad options existing already in the hybrid space, we might well ask why a new tool is justified, why specifically it ought to use an uncommon language, and why it should be embedded in Max specifically rather than some other platform or language. To answer these questions, first we will look at my personal motivations, and following that, at why I chose Max and s7 Scheme to fulfill them.